One family's freight house story, etched in stone

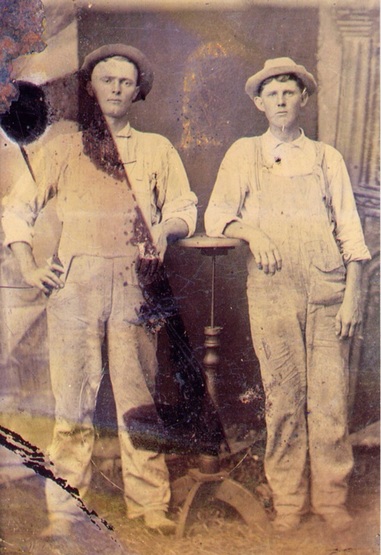

George and William Boyles. Photo courtesy Dennis Boyles

George and William Boyles. Photo courtesy Dennis Boyles

By BRUCE SCHWARTZ,

Board Member, Discover Lansdale

From a distance, the stately freight station looks solid enough, from the peak of its roof to the ground, untouched by time.

But you have to get close – nearly nose to the stone – to appreciate the timelessness of the building, and the craftsmanship and care that went into this rock of Gibraltar along Lansdale’s South Broad Street.

Except where joists and loading docks had been connected, there’s hardly a crack in the cement or a chip out of the stones. They fit together as tight as Tetris blocks. It looks like it was constructed yesterday. Not 114 years ago.

“And this thing will be sitting here for 200 more years, unless they have an atomic bomb blast,” says Lansdale’s Dennis Boyles, who has more than a passing familiarity with the stonework here. His great grandfather, grandfather and great uncles all had a hand in building the freight station along the Philadelphia and Reading tracks in 1902.

Famous facades

Before his retirement, Dennis, 80, was a fourth-generation stonemason. His family’s craftwork can be seen in many of the area’s famous facades, from the Masonic Temple on Main (just sold by the borough to developers) to the old Methodist Church at 3rd and Walnut (slated to be demolished for upscale housing). Others, such as the old high school on Main Street and the Green Street School, both from around the turn of the 20th century, no longer stand.

But the freight house promises to be around a long time, and not just because Discover Lansdale purchased the building for preservation. The grey, squared granite stones of the exterior “were extremely hard to work,” Dennis explains, examining the walls. “They don’t yield. Neither do they weather, as you can see. They’ve been here a hundred years, and it doesn’t look as if they’ve weathered any.”

The vault-like walls are 18 inches deep, and in two layers. The outer, set in a block pattern called Ashlar, came from a quarry in Rockhill. The mortar used in those days was just sand and lime, not Portland cement, Dennis explains. “It takes 20 years for lime to get to its full hardness,” he says, but it lasts nearly forever.

The pointing is as intricate as the stonework, with raised ½-inch rules running between the stones. “It’s what you call ribbon-cut point,” Dennis says. “There’s hardly anybody who knows how to do that anymore.”

A super-solid structure

In the cavernous interior, in contrast, the work is “nothing fancy,” Dennis says. The stones of the inner wall, many from local quarries such as White’s in Lansdale, are all shapes and colors, and they look slapped in and cemented over. But that doesn’t make them any less solid. From the roof’s massive rafters to the unyielding floor joists, the interior seems impenetrable, even to driving rain.

The official contractor for the freight house was George Boyles, Dennis’ great uncle. “He was older than my grandfather, and all his brothers had to work for him.” Their father, Dennis’ great grandfather Joshua J., was the first mason in the family. “Joshua didn’t like farming,” explains Dennis, and so hired on with a local stonemason to learn the trade after coming home from cavalry duty with the Union Army.

With Joshua J.’s advanced age and declining health, George and his brothers – Dennis’ granddad, William L., and youngest brother Joshua J. – did most of the work. And that was well before the era of forklifts and cranes. “It was all manpower in those days,” says Dennis. “Those stones are not light. The average size is maybe 10 inches square, and the weight maybe 15-18 pounds each. When you laid them all day, your back got tired.”

'Just an old piece of junk ... '

Apprentices and laborers helped with the inside, but the exterior work was all the Boyles. Nonetheless, construction took just about six months, from early April into October 1902. It opened a half-year before Lansdale’s passenger station, whose construction had started at the same time. And its 16 massive bay doors rolled open and shut for shippers well into the late 1970s, when they closed for the final time.

Dennis returned to the freight house in the ‘80s, to take photos for what he thought would be his last goodbye. “My wife said, ‘I have a feeling they’ll knock it down. It’s just an old piece of junk to them. So if you want your family to remember it… ‘ “

Now they and future generations will have a huge chunk of their history, and Lansdale’s, to point to with pride.

Board Member, Discover Lansdale

From a distance, the stately freight station looks solid enough, from the peak of its roof to the ground, untouched by time.

But you have to get close – nearly nose to the stone – to appreciate the timelessness of the building, and the craftsmanship and care that went into this rock of Gibraltar along Lansdale’s South Broad Street.

Except where joists and loading docks had been connected, there’s hardly a crack in the cement or a chip out of the stones. They fit together as tight as Tetris blocks. It looks like it was constructed yesterday. Not 114 years ago.

“And this thing will be sitting here for 200 more years, unless they have an atomic bomb blast,” says Lansdale’s Dennis Boyles, who has more than a passing familiarity with the stonework here. His great grandfather, grandfather and great uncles all had a hand in building the freight station along the Philadelphia and Reading tracks in 1902.

Famous facades

Before his retirement, Dennis, 80, was a fourth-generation stonemason. His family’s craftwork can be seen in many of the area’s famous facades, from the Masonic Temple on Main (just sold by the borough to developers) to the old Methodist Church at 3rd and Walnut (slated to be demolished for upscale housing). Others, such as the old high school on Main Street and the Green Street School, both from around the turn of the 20th century, no longer stand.

But the freight house promises to be around a long time, and not just because Discover Lansdale purchased the building for preservation. The grey, squared granite stones of the exterior “were extremely hard to work,” Dennis explains, examining the walls. “They don’t yield. Neither do they weather, as you can see. They’ve been here a hundred years, and it doesn’t look as if they’ve weathered any.”

The vault-like walls are 18 inches deep, and in two layers. The outer, set in a block pattern called Ashlar, came from a quarry in Rockhill. The mortar used in those days was just sand and lime, not Portland cement, Dennis explains. “It takes 20 years for lime to get to its full hardness,” he says, but it lasts nearly forever.

The pointing is as intricate as the stonework, with raised ½-inch rules running between the stones. “It’s what you call ribbon-cut point,” Dennis says. “There’s hardly anybody who knows how to do that anymore.”

A super-solid structure

In the cavernous interior, in contrast, the work is “nothing fancy,” Dennis says. The stones of the inner wall, many from local quarries such as White’s in Lansdale, are all shapes and colors, and they look slapped in and cemented over. But that doesn’t make them any less solid. From the roof’s massive rafters to the unyielding floor joists, the interior seems impenetrable, even to driving rain.

The official contractor for the freight house was George Boyles, Dennis’ great uncle. “He was older than my grandfather, and all his brothers had to work for him.” Their father, Dennis’ great grandfather Joshua J., was the first mason in the family. “Joshua didn’t like farming,” explains Dennis, and so hired on with a local stonemason to learn the trade after coming home from cavalry duty with the Union Army.

With Joshua J.’s advanced age and declining health, George and his brothers – Dennis’ granddad, William L., and youngest brother Joshua J. – did most of the work. And that was well before the era of forklifts and cranes. “It was all manpower in those days,” says Dennis. “Those stones are not light. The average size is maybe 10 inches square, and the weight maybe 15-18 pounds each. When you laid them all day, your back got tired.”

'Just an old piece of junk ... '

Apprentices and laborers helped with the inside, but the exterior work was all the Boyles. Nonetheless, construction took just about six months, from early April into October 1902. It opened a half-year before Lansdale’s passenger station, whose construction had started at the same time. And its 16 massive bay doors rolled open and shut for shippers well into the late 1970s, when they closed for the final time.

Dennis returned to the freight house in the ‘80s, to take photos for what he thought would be his last goodbye. “My wife said, ‘I have a feeling they’ll knock it down. It’s just an old piece of junk to them. So if you want your family to remember it… ‘ “

Now they and future generations will have a huge chunk of their history, and Lansdale’s, to point to with pride.